February 2023

Caesura Presents…Esteban Rodriguez

Esteban Rodríguez is the author of six poetry collections, most recently Ordinary Bodies (Word West Press, 2021), and the essay collection Before the Earth Devours Us (Split/Lips Press, 2021). His poems and reviews have appeared in New England Review, The Gettysburg Review, Colorado Review, West Branch, The Adroit Journal, The Rumpus, and elsewhere. He is interviews editor for the EcoTheo Review, associate poetry editor for AGNI, and a senior book reviews editor for Tupelo Quarterly. He lives with his family in south Texas.

Website: https://www.estebanrodriguezpoetry.com/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/estebanjrod11

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/estebanjrodriguez

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/ejrod11/

Doing the Hard Work of Writing and Deep Reading

John:

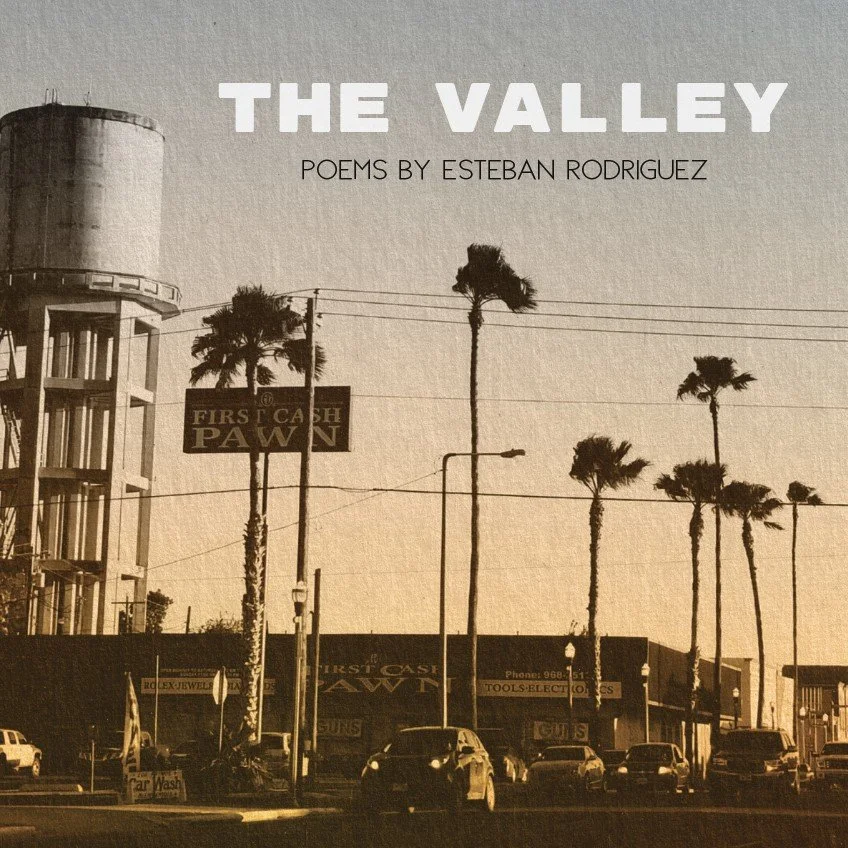

Esteban, before delving into your incredible poetry, I feel I must ask how you’re able to publish so many books in so few years. In only two years, you’ve published the poetry collections Ordinary Bodies (word west press), The Valley(Sundress Publications), (Dis)placement (Skull + Wind Press), In Bloom (Stephen F. Austin State University Press), and the essay collection Before the Earth Devours Us (Split/Lip Press). That’s about as prolific as I’ve ever encountered. Can you speak to how you’re able to write this much, this consistently well, and, with all your work so thematically linked, with such a tight focus without ever falling into redundancy and poetic repetition?

Esteban:

Thank you so much for speaking with me, John. And thank you for your kind words. I’ve been fortunate enough to publish in a number of journals and great presses, and to be honest, I’m not sure I could have ever envisioned the success I’ve had putting my words on the page and sharing it with the world. I’ve always liked the quote, “Success is when talent meets hard work,” and while I can’t necessarily speak to the full extent of the talent part, I can definitely speak to the hard work part of that phrase. I think poetry, and writing in general, can tend to be thought of as separate from one’s day-to-day job, even if that job is teaching literature or creative writing. But I can’t help but think of poetry and writing as work, not in the capitalist sense of producing something for monetary benefits, but rather the sense of creating a new thing for the benefit of itself, and hopefully for the benefit of others. When I first began writing, I was under the impression, as perhaps other young writers are, that I would write only when inspiration came to me, or when some outside event happened that prompted me to put pen to paper. The poems that resulted from that mindset were never truly realized, and I quickly learned, thankfully, that I had to have a certain amount of discipline to achieve results. I wasn’t putting anything on a spreadsheet, but I was finding that if I was reading and writing intentionally, I would yield some great lines, and hopefully something that resembled pretty good poetry.

I think another reason I’ve published quite a bit stems from the fact that I’m always writing toward a project, even if the project is just in its infancy and hasn’t quite been fully fleshed out. There is only so much time on this earth, and I can’t see myself writing something that won’t be put into a collection in some shape or form. This doesn’t mean that I don’t experiment with themes or that every poem or nonfiction piece I write is publishable the moment that it is done, but it does mean that I have an idea of what it could be and how it could contribute to the larger project as a whole. The projects definitely change as more pieces get written, so I do try to be flexible with the reality of what can be accomplished.

As far as avoiding redundancy in my work, I will say I do write about a lot of the same subjects (father/mother-son dynamics; the physical and emotional uncertainty of border landscapes; the attempt to find meaning in the mundane), and I do fear at times that I can be exhausting a theme unnecessarily. But every time I write about my mother or father, or I detail the region where I was raised, I can’t help but think that maybe I’m doing something akin to what musicians do with different versions of certain songs. Sometimes the acoustic version says what the original can’t. Sometimes the live version conveys what the recording never could.

John:

Thank you for sharing your thoughts on your projects and the hard work it takes to write consistently. I also appreciate your fears on exhausting a theme. We all write about what haunts us, what keeps us up at night, what we cannot notwrite about. But those things, emotionally complicated as they are, do tend to explore the same themes so risk a degree of redundancy.

As a reader can only be surprised by a poem if the poet themselves are equally surprised by what they wrote, how do you keep yourself in that constant state of creative awe? I notice you often play around with forms in The Valley (from prose poems to couplets to lack of any punctuation), which is one way of keeping things fresh. How else do you keep pushing yourself, testing and adding to your skills and vision, while circling around the same themes?

Esteban:

I’m always reading. There is no way that any writer can fall into a creative slump if they are constantly reading. I’m not sure if I believe in writer’s block, at least not the way it is romanticized in the public sphere (a writer like Fran Lebowotz comes to mind). This is not to say that I don’t fall into creative frustrations, where I feel, as mentioned above, that I’m writing about the same theme excessively. But the beauty of being a writer is that you are first and foremost a reader, and there are so many books, new and old, that one can learn from. For example, this year I thankfully discovered the work of the French novelist Claude Simon, the 1985 Nobel Laureate in Literature. I think it would be safe to say that his work doesn’t grace most people’s bookshelves here in the States (besides The Flanders Road, published by New York Review Books this year, it can be quite difficult to find his books translated in English), but discovering his novels has challenged the traditional books I read, since his stream of consciousness style coupled with his themes of conflict, violence, and the search for meaning in the face of chaos and destruction, was not something I was used to seeing on the page. Reading his works made me think more about how to go about incorporating multiple themes within a poem or personal essay, and how the individual line can drive the momentum of a piece. Creative awe starts with discovering what has been done and realizing that you as a writer can expand or create something entire new from that. As long as there are books, there is a source of inspiration.

In The Valley, a majority of poems were written as a direct result of reading W.S. Merwin. I felt as though I was essentially stealing his style, or at least riffing off it so much that it would be noticeable when I submitted these poems for consideration to journals. But doing so allowed me to look at the line differently, to wonder how emphasis is placed on an individual word, and how a reader can interpret the meaning of certain phrases when there is no pause. The way I read any given poem in the collection can be different from the way you do, and years down the road, we might read that same poem differently again. Nevertheless, poetry is amazing in this aspect, since it invites readers to invest themselves in the totality of the poem. If I was trying to do anything in The Valley, it was giving readers more room to interpret the poems in their own way, to feel as though they have a stake in the narrative and outcome.

One thing this book did have that previous collections didn’t were photographs. The Rio Grande Valley, located in south Texas along the U.S.-Mexican border, is quite a unique region (as all regions essentially are), and I wanted to illuminate that with photos of the area, which my mother and sister were gracious enough to take. I’m an admirer of the work of W.G. Sebald, and the manner in which he uses photos throughout his novels is engaging and fascinating. The photos are not merely complements to the text, but rather a part of it, and I too wanted to do the same with this book. I extended this to Ordinary Bodies, and I definitely foresee my writing being enhanced with photographs in the future. Perhaps the next step is to experiment with visual text and bring the page to life, more so than what the words are already doing.

John:

I’d love to know about your process of composing poems inspired by photography. I adore and often write ekphrastic poetry, and I’m interested in how others approach it. You say that the photos are “not merely compliments to the text, but rather a part of it.” Can you tell me more about this? How do you incorporate so deeply the image into the text, how do you spark that necessary conversation? And practically, how do you start that conversation? For example, do you start with a stark image or details from the image and build the poem up from there?

Esteban:

I must say, I’m by no means a photographer. I’ve always wanted to get into the art form, but I’ve always found a way to convince myself not to get a camera. In The Valley, there is actually only one photograph that I took myself, which is of the beach at South Padre Island. The rest of the photographs were taken by my sister and mother. I was living in Austin at the time, and I had a vision of what I wanted the photographs to capture. My mom had just retired, and my sister was going to school, so they spent the summer going to the various locations that I had assigned them. I was actually writing the poems simultaneously with the photographs. But I never wrote the poems in response to a photograph. Rather, the poem was independent of the image, but with poems like “McAllen” or “El río,” I knew beforehand what the photo was going to look like, even before my sister and mother sent it to me. So, in a way, I had an image of what the poem could be, and when I did receive the photographs, they met all my expectations and more.

Now, I have written purely ekphrastic poetry, specifically during grad school, and a whole section of my thesis was dedicated to ekphrastic poems centered on the artwork of Francis Bacon, Michel Duchamp, Salvador Dalí, and Andrew Wyeth. I haven’t returned to that particular type of writing in over a decade, but I do have a project in the works that will be composed entirely of ekphrastic poems (the working title is Secondhand Forgeries). The poems that I wrote in grad school combined personal elements with historical facts about the painting (its composition, its impact, etc.), so I always started with studying the painting, the artist, and how such an idea for the artwork came to be. I wanted to be an artist when I was in my teens, but unfortunately, I was dissuaded by my parents because they thought it wasn’t a viable career option (to spite them, I decided to make less money by being a poet; just kidding, but not really). Nevertheless, art is still something that I hold dear to my heart, and although I will occasionally dabble in a few pieces from time to time (collages, doodles), I’m too deep within poetry and all things literary to commit more time to another medium. Maybe one day I’ll find a way to mesh the two completely.

John:

What an interesting and unique process; thank you for discussing it with me.

If you don’t mind, I’d love to shift gears and discuss some of the themes in The Valley. There’s a line in “Recuerdo: Wardrobes” that encapsules so much of your work. You begin the poem with:

Because treasure is found in darkness

To me, being quite familiar with all your work, this single line resonates clearly across your years of writing. It seems, like me, you’re always seeking those sharp shards of light that give context and meaning to the darkness of our poems. Could you tell us how you see the interplay of light and dark (both mixing and contrasting) in your poems and how you’re able to retain that constant treasure-seeking in a world (and poems) so often stained in struggle?

Esteban:

I’m so glad you mentioned this poem, which might be the oldest poem in The Valley. I wrote this poem when I was a tutor at a high school, during some downtime we had toward the end of the semester. And it’s a poem that has kept coming up throughout the years, begging for revision and a fresh, but older, set of eyes. It finally fit in perfectly with this collection, and I think you do hit the nail on the head when you say that it encapsulates that interplay between light and dark in the rest of my work. In “Recuerdo: Wardrobes,” the speaker discovers his mother’s old dresses and ponders how his mother’s body has changed over the years. He also contemplates his father’s wardrobe, the hardhats and boots and Levi’s that have come to define him. And yet, despite all their implications, the speaker cannot help but want to recreate scenes that may or may not have existed because he wants to keep the image intact. That is definitely what I’m doing with my poetry, trying to keep the past intact, and often that means discovering something throughout the course of the poem. What comes to light might be a realization that the speaker’s heritage is different from those who share similar last names (“Fence” from Dusk & Dust), or it might stem from the speaker standing in the backyard with his father, wondering if that mythic beast of la lechuza is real (“La lechuza” from In Bloom), or it might merely be looking at Tupperware and pondering all its cultural and social implications (“Ode to Tupperware” in Crash Course). Pulling back the folds of darkness that enshroud memory should always be a poet’s job. I hope I’m doing my role, and that in the process I’m illuminating the treasures of self-discovery, knowledge, and awareness that too often hide in darkness.

John:

There’s so much to unpack in this statement, and I would like to ask a dozen questions stemming from it. First, though, let’s discuss this idea of keeping “the past intact” and how that relates to the speaker’s cultural voice in these poems. For example, a few lines I’d like to focus on:

Dispute the name not the settlements (from “Mercedes”)

Because secrets age into gossip …

He can uncover what a body / he’s long oppressed (both from “Harlingen”)

Can you speak to how the speaker in these poems relates to both personal and cultural history?

Esteban:

One of the things that I’ve always tried to do with my poetry is to make the speaker an observer who, throughout the course of a poem, realizes he has more at stake than he initially thought. The poems that you mentioned above differ slightly in their themes, but they are related in the ways in which the speaker is attempting to understand the world, which isn’t always easy to accept. In “Harlingen,” for example, the speaker hears from his mother that his younger cousin has tried to scrub his skin till he rids himself of his darker complexion. There is not any definitive indication that there is any truth to this, other than the gossip that the speaker’s mother engages in, but the hearsay is enough to spark reflection on his own skin, how much lighter it is than his mother’s and how he is able to pass for white. As in most of my poetry, the speaker finds a way to connect the outside world to his own experience, thereby making the historic, even if it is rooted in secrets or gossip, become personal.

The speaker in “Mercedes” looks at the history of this town named Mercedes and examines how it went from essentially a plot of land people were settling into to the home of the Stock Show, which is an annual event that includes a carnival and rodeo in the Rio Grande Valley. I’m not sure you would find a whole lot of people who could comfortably detail the history behind this town (it was apparently named in the early 1900s after the then Mexican President Porfirio Díaz’s wife, in her honor), especially one that is as small in size and population as Mercedes is. Its nickname is “Queen City,” which is the title of another poem in The Valley, and here, the speaker ponders the “pride in naming a piece of land.”

Perhaps that is the only way to keep the past intact, by making situations and events personal to the point that there is no avoiding how they make you feel.

John:

I absolutely love and wholly agree with, personally and creatively, with that last statement. What makes history resonate best in a poem is when it’s deeply connected to the speaker’s (or another character’s) emotional landscape. We need to see how the past impacts the present (or future), how it reaches its often-ugly hands out to reach us now. Similarly, I see a lot of generational family shifts in your poems, so many fears of how the past continues to influence us and what we might be passing down to future generations. I’d like to quote a line from your longer, multi-sectioned poem “El Río”:

Spoken to in a language of doubt / and dragged to a place where you eventually can view your once-father promise him to / not suffer such fate

Can you speak to how generational family trauma and fears play such a pivot role in your work?

Esteban:

I’m not sure I understand the full extent of my family history, at least the way that others can point to a geographical area or important figure or an momentous event that helped define their family. From what I know, my grandmother was from Mexico, and my grandfather’s family had lived in south Texas for generations. So there is always that mystery that looms over my origins. But in reality, that’s never affected me to the extent that my immediate family’s history has impacted me, specifically the way in which my mother was expected to fulfill a more submissive role growing up, and how my father (who is actually my stepfather) crossed into this country with the hopes of starting a new life.

Over the years, both of them have given me glimpses of what their lives were like in the past, of their relationships with their parents, of their interactions with the places they lived, of how they view the world on both practical and philosophical levels. But they have never spoken about important details and events enough for me to paint a complete picture. For example, my father has not talked about the conditions in Mexico that led him to cross the river, and my mother, who I’m not sure knows fully either, has not divulged any details other than dividing his existence into the phrases “before he came here” and “after he came here.” Perhaps that’s the reason why my poetry and writing centers so much on them. I’m trying to fill in the gaps their silences have left, hopeful that it will create a narrative that accounts for what they have not said, and that others, who have experienced that same silence, can relate to, even if just a little. I never went through what they had to endure, but that doesn’t mean I can’t write about it as an observer, as someone who seeks to understand others so he can understand more about himself.

John:

I deeply appreciate your statement “I’m trying to fill in the gaps their silences have left.” I feel that’s appliable to pretty much everyone. We are all trying to piece ourselves together into a whole via filling in gaps left in the wake of whom and what came before us. It reminds me a bit of this line from your poem “Recuerdo: Wardrobes”:

and twirl / my mother’s image around before it slips / from its threadbare form

There’s a delicate balancing act here between the concrete and the ephemeral, the defined and the not-yet-defined or inherently undefinable. I sense throughout The Valley that you’re trying so hard to find (or perhaps, more accurately, forge) certainty and concreteness in a very uncertain and often edgeless world. Can you speak to how you use so much concrete detail and imagery in your poems? Do you feel the concrete works as anchors for your larger, more ambiguous themes?

Esteban:

If there is any praise that I’ve consistently received over the years, it’s always been my use of imagery. And I always find it incredibly interesting because I never really thought that I was using imagery to the extent that I was. I just saw myself as writing, but upon reflecting more recently on what I’ve published over the past decade, I’ve realized that imagery was always driving the narrative of a poem or essay.

I’m always seeking to put forth images that operate on two levels: description and meaning. I remember taking a poetry workshop back in grad school, and during a critique of a poem by one of our fellow students, my friend Daniel praised the imagery of the piece, yet he wasn’t sure what all of it meant. That always stuck with me because while we were in awe of the descriptions in the poem (I believe in it the speaker was pushing away branches and going deeper into the woods, located in the back of their house) we were confused about how we should feel. So, imagery has to evoke a response within a reader who might not know the full extent of what is being described.

At this time, I hadn’t completely found my poetic voice yet. I was experimenting with different personas and different styles. I was reading a lot, however, and it wasn’t until I read The Crying of Lot 49 by Thomas Pynchon that I discovered what imagery could truly do. Now, Pynchon might not be the most likely source of inspiration for an aspiring poet, but there is a passage in the beginning of the book describing Mucho, Oedipa’s husband, and his previous work as a used car salesman (the passage starts, “Yet at least he had believed in the cars” and ends with “Endless, convoluted incest.”). It’s one of the most fascinating instances of imagery I have ever encountered, and as I’ve reread The Crying of Lot 49 over the years, I still can’t help but be in awe of that passage, of how Pynchon describes these cars and the people who owned them and how the things that were left in them when they were traded were just a “futureless, automotive projection of somebody else’s life.” Pynchon made it seem so easy, and I wanted to do that as well.

I do, however, love the surreal, and often times you can find mannequins, scarecrows, sword swallowers, bearded baronesses, and a range of other odd characters and objects that become the center of a hallucinatory journey. “El río” in The Valley has the surreal quality to it, and while it might take some time to tease out exactly what is happening, including those uncanny characters and objects (like the ones mentioned above) ground the narrative a bit more, and hopefully produce a slightly uncomfortable feeling within the reader. After all, poetry should make you feel at least somewhat uncomfortable. It should provoke a response when you least expect it.

John:

Imagery also tends to drive much of my work, and I whole-heartedly agree that poetry perhaps should make the reader slightly uncomfortable, at least uncertain. If the poet isn’t surprised at their own work, how could a reader be? Do you find yourself surprised by your own work? When composing a new poem, do you have an idea of where it’s headed, or do you let the poem find itself during the writing process?

Esteban:

I used to be much more surprised than I now get, simply because it always felt like such a miracle to not only complete a poem, but to look back at it the next day and feel happy that it came out the way I wanted it to. This is not to say that revision wasn’t a part of the process (hardly any poem came out perfect when I had finally finished it), but I got excited that the form was there, that all the parts I had obsessed about for days, even weeks, were realized into words that I arranged into meaning. During those first few years as writer m, no past poem guaranteed the completion of a future poem, so I never took them for granted. Now, that surprise doesn’t hit me as much, but it’s because I know that “miracle” is really hard work and determination. I created it, and I’m confident that I can again.

But one major change now is that I don’t always know where a poem is going or where it will end. This may seem somewhat contradictory, but in the past, I knew exactly what word or phrase was going to end a poem. Now, I’m not too certain, and there are times when I have to erase lines I grew to love because they don’t fit with the overall intention or feeling of the poem. In a way, this makes it much more exciting because it allows me to spend more time with a poem and ensure that it’s exactly what I want. Regardless of any uncertainty that may creep in during the journey of writing a poem, I know that I will help guide it to its eventual end, that I will make sure it has a place to rest its head.

John:

That transition is so interesting. I’ve never once known where a poem was going, so hearing that you long have had an intended ending but now feel less certain (and more excited) is fascinating to me.

This seems like a perfect last question, and thank you so much for this intriguing discussion. As your process has been changing recently, do you have a new collection in the works or new poems that utilize this fresh, uncertain, exciting approach? How do you feel your new and upcoming work differs from what’s come before?

Esteban:

Thank you so much for such amazing questions, John. I have two collections that I just completed, The Lost Nostalgiasand Love Song at the End of a Burning Empire. While The Lost Nostalgias is reminiscent of my older work (with many of the poems written between 2013 to 2017, but revised just this year), Love Song is more reminiscent of my collection (Dis)placement. With a surreal lens and a narrative focus that finds scenes of brutality and tenderness on equal footing, Love Song at the End of a Burning Empire aims to contemplate love amid seemingly never-ending strife, traversing between the half-lucid confines of a bedroom, the uncertain landscapes of ancient civilizations, and the ruins of a city suffering the aftermath of conflict and destruction. The book is dedicated to my fiancée, Stephanie.

Lately, however, I’ve been writing more personal essays, and I am working on two collections, More Than I Could Chew, which is centered on various episodes during my childhood where I found myself emotionally and physically overwhelmed, and Lessons on Inheritance, a collection that looks at my mother's body through my eyes and that specifically examines her fight with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, her remission, and her recent recurrence.

I have ideas for a few other projects as well, and hopefully when we speak again, I’ll have more work to talk about with you. Thank you again, John.