May 2023

Caesura Presents…Kimberly Kralowec

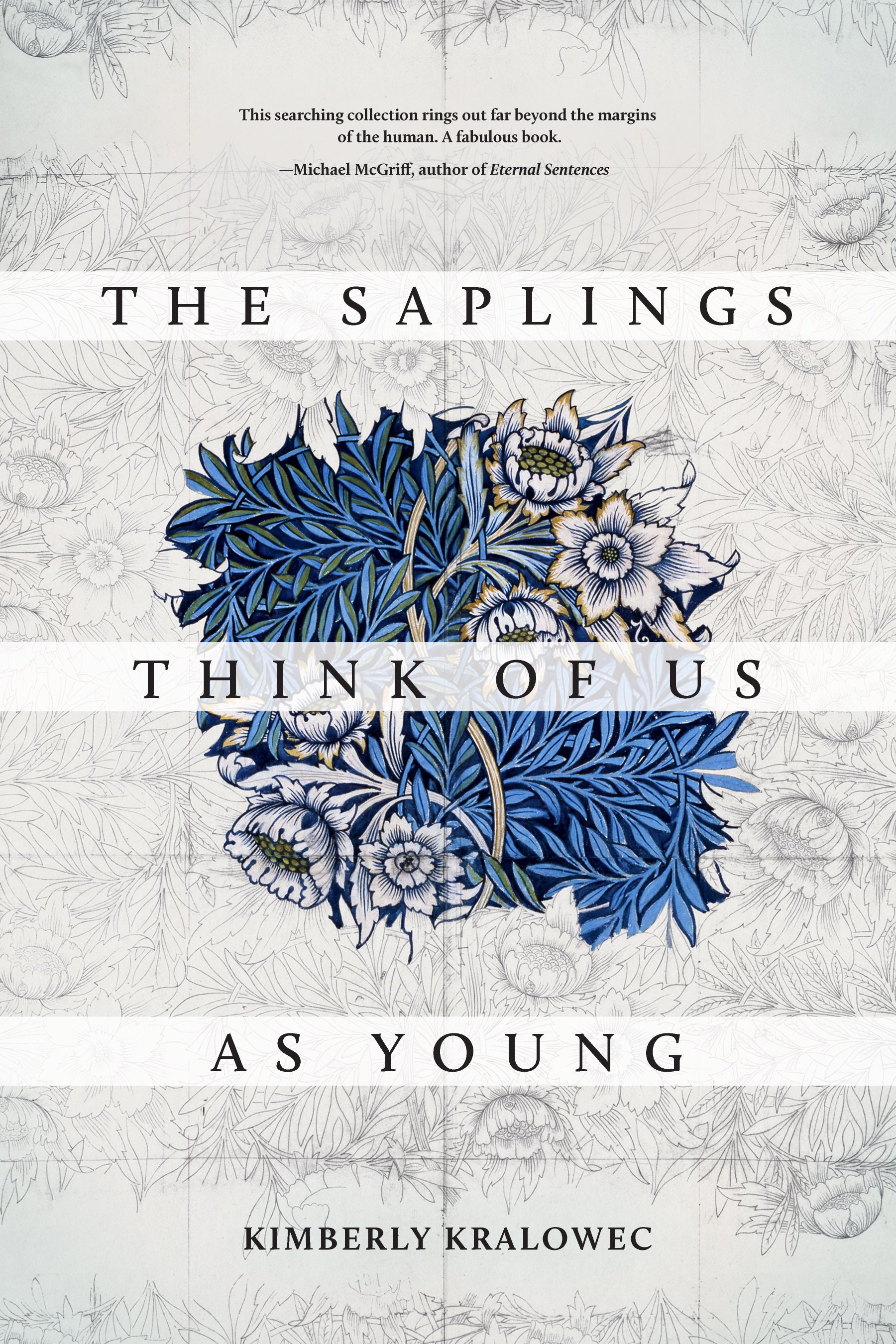

Kimberly Kralowec is the author of The Saplings Think of Us as Young (Kelson Books, 2023) and a chapbook of love poems, We retreat into the stillness of our own bones (Tolsun Books, 2022). She was a finalist in the 2023 North American Review James Hearst Poetry Contest, the 2022 American Literary Review Poetry Contest, and the 2021 River Styx International Poetry Contest. A lawyer by profession, she lives in San Francisco.

Website: https://www.anapoetics.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/kkralowec

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/kimkralowec/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/kimkralowec

Pre-Order at:

https://www.kelsonbooks.com

Kelson Books, forthcoming in May 2023

From a Perspective of Smallness

John:

Congratulations on the publication of The Saplings Think of Us as Young! It’s such a beautiful, intimate, nuanced work. Saplings portrays great honesty and vulnerability and balances the dual need to observe and participate in a greater world. Speaking to his dual need, how do you spark that balance of pure observation and direct human participation in your poetry? And in the world of these poems, what does it mean, truly, to “participate?”

Kimberly:

Thank you, John! It’s a pleasure to be a part of your interview series. It can be difficult for poets to observe the world without strong feelings of participation in it. Denise Levertov wrote that poets must “live with the door of one’s life open to the transcendent, the numinous.” This is an aspirational goal for my poetry and a central idea that drives my work. For me, “participation” means drawing out of lived reality a heightened experience that can only be expressed in poetry (or other art forms). I hope that readers of Saplings will share in the experience I’ve tried to translate from my observations of this beautiful and damaged world.

John:

And you show us a beautiful yet damaged world in the very first lines of this collection, from the aptly titled “Beauty Always Extracts a Price”:

All the world is an urgent fire warning—purple

lightning in human profile, caught in glorious

photos of famous skylines.

Throughout Saplings, we get a sense of the interconnectedness of the human and natural worlds. Did you initially set out to write a collection that feels so thematically consistent or did you just write and write and end up finding common threads weaving throughout each poem?

Kimberly:

I didn’t set out to write thematically related poems. Sometimes it feels like the themes in Saplings chose me, rather than the reverse. Most of the time I feel only gratitude that a poem chooses to emerge at all. The poems in Saplings were largely written before I realized they could work together as a manuscript. I tried many different groupings and sequences, and through this process learned that ordering really does shape a collection’s meaning. Once I understood where the manuscript was headed, I was able to lean into those themes as some of the newer poems came together. I also revised certain older poems to better fit the collection.

John:

That makes sense, and it sounds a lot like my process.

As you point out, “ordering really does shape a collection’s meaning,” and I’d love to know what journey you hope readers are carried off on over the course of Saplings. What larger meaning does the collection build toward?

Kimberly:

The earliest poems in Saplings emerged as an exploration of intimacy—of close relationships and private spaces and the liminality of those spaces. Together with an intimate other, the “we” of the collection attempts to grapple with intrusions into those spaces—in particular, intrusions of illness and of climate change, the collective harms we’re all relentlessly undergoing. The speaker in Saplings experiences the natural world from a perspective of smallness and youth—what might be called “deep time”—and also, essentially, of love.

John:

Given the intimacy of these poems, may I ask how closely related they are to your lived experiences and in what ways they are fictionalized for emotional effect? I always find this question fascinating, as many poetry readers assume a first-person voice in a poem must be the poet herself. Yet, I would consider poetry more fiction than non, being based more on larger truths than experiential details. So, how much of Saplings is based on your life and how much is metaphor meant to explore those larger truths within all our experiences?

Kimberly:

All the poems are based in some way on what I’ve observed or experienced in my own life. I always challenge myself to use my imagination to heighten real-life remembered moments as much as I can. I don’t think of this as fictionalizing those moments, but as attempting to amplify true-life perceptions and lived experience in service of larger truths. For example, the first line of “Hermetic”—“It’s one of several possible todays”—is not literally true, and it’s not a metaphor, but for me it expresses a true-to-life, non-fictional feeling that I hope readers will recognize. “Hermetic” interweaves reflections on California’s drought with emotions experienced when I was a caregiver for my husband during a serious illness. The observations are very disguised, I suppose, but I consider them all true, not metaphorical. If a poem successfully expresses a larger truth, that’s not fiction, is it, regardless of the poet’s methods?

John:

And you do an excellent job of sparking fresh connections between apparently disparate things, such as California’s drought and caregiving. Almost all your work uses landscape and climate in ways that feel deeply personal and intimate to the emotional world of its characters. Given its many similarities to ecopoetics, which poets do you enjoy that similarly converse with the earth and how humans tend to affect it?

Kimberly:

I love the cosmic scale of Mei-mei Berssenbrugge and the grounded, earthy poems of Brigit Pegeen Kelly. Brenda Hillman urges poets to “revise into strangeness” and it’s wonderful to read her work with the idea in mind that she has done this herself. Stones of the Sky by Pablo Neruda (translated by James Nolan) showed me a poet’s imagination melding the natural world with human experience and perception in a symbolic way.

John:

Ah, I love Berssenbrugge’s work too, and I’m pretty familiar with Hillman’s poetry. Thank you for introducing me to Kelly. What other poets have influenced you over the years? What have you learned from them?

Kimberly:

I have been heavily influenced by poets such as Tomas Tranströmer, James Wright, Pablo Neruda, and Leonardo Sinisgalli, whose work achieves moments of heightened perception, asking the reader to accept ideas that cannot literally be true in order to experience reality, or “truth,” in new ways. I’ve studied Emily Dickinson, Sylvia Plath and Lynda Hull closely, and among contemporaries, some of my favorite poets include Louise Mathias, Sara Eliza Johnson, Kimberly Burwick, Sarah Rose Nordgren, Michael McGriff and Danusha Lameris. What I love about all of these poets is how they challenge the reader to experience ideas in fresh ways.

I’ve also had the privilege of working with some outstanding poet-teachers, especially Jeanine Walker, who teaches through the Hugo House, and the late Eavan Boland, who was a workshop leader at the Napa Valley Writers’ Conference. One lesson I learned from my teachers is to be open to feedback but also trust my instincts and stay true to my own intentions for my work. I like being challenged when I read poetry, and over time I’ve become more comfortable with the idea that my poems might sometimes challenge the reader. At the same time, I’ve learned to stay aware of the line between mystery and confusion.

John:

Finally, Kim, I’d like to ask what’s next for you? Are you working on a new collection? Are there any new themes or structures you’re experimenting with? What can we expect from you in the future?

Kimberly:

To shake things up, I’ve been trying out different approaches to composing poems. For example, there’s Ellen Bass’s “controlled chaos” method, which I learned from her Living Room Craft Talks, and David Biespeil’s “word-palette” method, discussed in his wonderful book, Every Writer Has a Thousand Faces. I don’t know what will come from this, but I’m hoping different styles of writing might emerge from trying out new methods of composition. Right now, I’m focused more on individual poems than on compiling a manuscript, but I hope a second collection might start to emerge soon. Over the next few months, I’ll be spending time shepherding Saplings into the world, which, as I’m sure you know, is a project that uses a very different part of the brain.

John, it has been a pleasure doing this interview with you! Thank you for inviting me to participate.